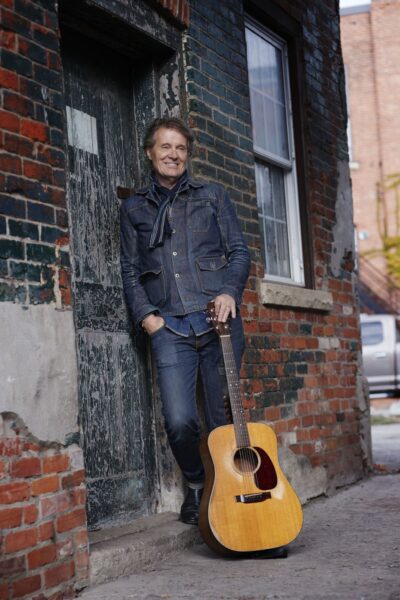

Walking down Russell Hill Road in the tony Forest Hills area of Toronto, towards the impressive residence of Rush drummer/lyricist Neil Peart, I was reminded on several occasions by Anthem President Ray Danniels, to always be fully prepared for any inquisition with Mr. Peart.

On hearing about his sad demise on Tuesday, January 7th in Santa Monica California following a 3½ year battle with brain cancer (technically, glioblastoma) at the age of 67, I relived fond memories of a number of chats we engaged in for Music Express Magazine and how Danniels’ comments held true in that my pre-interview research stood me in good stead for our conversations staged in his upstairs attic office.

If memory serves me correct, I executed at least three interviews with Neil around the release of `Grace Under Pressure’ (1984), `Power Windows’ (1987) and `Roll The Bones’ (1991). In all three conversations, we were able to engage in some intellectual chatter about Rush’s various thematic concepts but it was outside topics like Peart’s passion for motorbike travelling which really piqued his interest.

After discussing `Roll The Bones’ lyrical theme about elements of chance defining aspects of life, Peart enthused about a recent trip he had just completed through China and how he was able to achieve a whole new respect for the local culture he encountered.

Recognized as the fourth-best drummer in rock music history by Rolling Stone Magazine (behind Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham, Cream’s Ginger Baker and The Who’s Keith Moon), Peart is lauded for his technically proficient, animated live performances and his insightful and poetic lyrics which created a series of conceptual releases which defied the requirements of commercial radio.

Yes, under Peart’s lyrical direction, Rush did score a number of hit singles with “Tom Sawyer”, “The Spirit Of Radio”, “Subdivisions” and “Time Stand Still” (with Aimee Mann) but it was the overall sonic grandeur of albums like “2112”, “A Farewell To Kings” and “Moving Pictures” which established Rush as a world-class band that was deservedly inducted into The Rock N Roll Hall Of Fame in 2013 (they were inducted into Canada’s Music Hall Of Fame in 1994).

Along with guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist/keyboardist/ lead vocalist Geddy Lee, Peart conspired to create 18 of 19 studio albums, 11 live albums and 11 compilation albums, winning seven Juno Awards and being nominated for eight Grammy Awards in the process.

Lee and Lifeson’s instrumental expertise had much to do with the band’s overall success but it was Peart’s percussive skills and lyrical prowess which created a uniqueness about Rush which had contemporaries waxing their admiration in a long list of accolades that were evoked by his demise.

Former Nirvana drummer and current Foo Fighters’ frontman, David Grohl said it best in a statement to Rolling Stone Magazine “Today the world lost a true giant in the history of Rock And Roll, an inspiration to millions with an unmistakable sound who spawned generations of musicians (including me) to pick up two sticks and chase a dream. A kind, thoughtful, brilliant man who ruled our radios and our turntables, not only with his drumming but with his beautiful words.”

After a less than successful self-titled independent debut album in 1974 (Moon Records) which featured original drummer John Rutsey, Rush earned a bit of a break when one track, “Working Man” was added to the playlist of Cleveland’s WMMS by station director Donna Halper. This promoted Mercury US to re-release the album and triggered Rush’s first U.S tour. At that point Rutsey quite the band stating his diabetic condition and reluctance to travel, paving the way for the emergence of Neil Peart to take over the drum kit for those first U.S dates.

Peart not only added his unique percussive style to the band but also assumed the mantle of chief lyricist, an input which was immediately struck with the release of the band’s second album Fly By Night which established the band’s progressive rock direction.

I was working at the Calgary Herald sports department at the time of the Fly By Night release but was also moonlighting as a record reviewer, helping out the paper’s resident music critic Eugene Chadbourne with the weekend entertainment supplement. He handed me this album with a Snowy Owl motif on the cover, and noting the trio was a Toronto outfit, I gave it a spin. But to be honest. I couldn’t figure these guys out, lyrics like the mini-saga “By-Tor And The Snow Dog” left me cold, and their follow up `Caress of Steel” which featured just five elongated tracks appeared to me to be even more derivative.

Yet the band seemed to be picking up traction with their 1976 release “2112” and, after launching the debut issue of Alberta Music Express in October 1976 (which included a short feature on the band) I was invited by Polygram’s Western bureau chief Ken Graydon to check out Rush who was on one of their first Western swings at the Calgary Corral. Again, I reluctantly agreed to attend but couldn’t see what all the fuss was about. I found Geddy Lee’s high pitched vocals to be jarring and although I could see the merits of their instrumental prowess, I just could not fathom their apparent appeal. Triumph had also come to Calgary around the same time and “Ontario Hydro” as I nicknamed them were as equally effective live but also delivered some commercially accessible songs.

This opinion of Rush changed drastically when Music Express moved to Toronto in early 1980. The band’s label, Anthem Records, were extremely supportive of our magazine and I was soon making a succession of treks up to their Oak Ridges HQ where Danniels and Marketing Director Tom Berry played me the bands latest tracks such as “Tom Sawyer”, “The Spirit Of Radio” and “Subdivisions”.

This was more like it, and as I began to get to know all three members, especially Peart, I could appreciate just how progressive they had become. Peart was especially amicable if he felt you knew what you were talking about and like a university professor discussing some important thesis, he could articulate the most amazing lyrical ideas and themes that he formulated into Rush albums.

Sadly, Peart encountered a series of personal tragedies with the loss of his daughter Selena in a 1997 single-car traffic accident on Highway 401 near Brighton On. Followed by the death of his wife, Jacqueline who died from cancer just 10 months later.

This forced Peart to take a leave of absence from the band, undertaking a 10-month global bike sojourn which he turned into a best-selling book titled “Ghost Rider, Travels On The Healing Road”

Peart returned to the band for their `Vapour Trails’ album in 2002 and although Rush executed two more studio albums; `Snakes And Arrows’ (2008) and `Clockwork Angels (2012), a couple of live albums and a series of box set re-releases, Peart announced his retirement in 2015, only to engage in a more pressing battle against brain cancer which he lost on January 7th, leaving behind wife Carrie Nuttall and daughter Olivia.

© All photos copyright of www.hopephotography.com