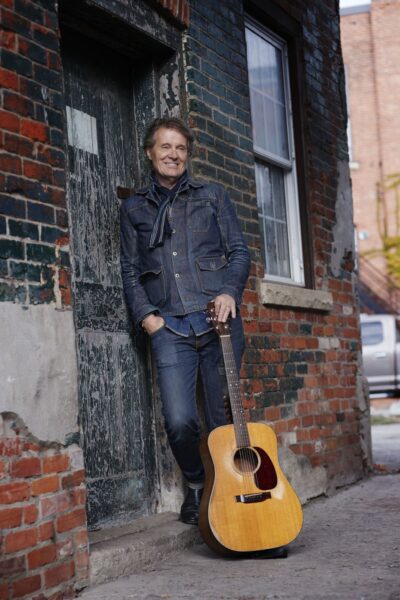

My first interview with Red Rider’s lead vocalist Tom Cochrane provided a source of confrontation. Red Rider; comprising of Cochrane (guitarist/lead vocalist) Jeff Jones (bass), Ken Greer (guitar) Peter Boynton (keyboards) and Rob Baker( drums) were a hotly sought after Toronto band in 1979. Both Capitol’s Deane Cameron and Anthem’s Ray Danniels were vying for them but Cameron was concerned that if Danniels signed them, distribution would go to PolyGram. Bruce Allen entered the picture seeking a mega deal from Capitol to sign Prism who had just enjoyed major success with their “Armageddon” release.

Unfortunately, Prism’s label GRT had just gone under and Allen was looking for a new label. Cameron agreed to sign Prism if Allen would also take Red Rider. Switching a Toronto-based band to a Vancouver-based management company wasn’t an ideal scenario and Red Rider wasn’t Allen’s type of band. He championed arena rock bands like Prism, Loverboy and Adams. Bands you could easily fit on a U.S concert tour with his Don Fox packages like Kansas, Heart and Foreigner. However, Red Rider was devoid of on-stage charisma. They just stood there and played like Pink Floyd or Supertramp. But they weren’t your typical Bic-flicking outfit.

[quote]“Would everyone please shut the f**k up. Otherwise we’ll be here all night.”[/quote]Red Rider released their debut “Don’t Fight It” album in March 1980. First single is a track called `White Hot’ which contains a lyric about some gun runners in Tanzania. I didn’t get it and wrote a pretty tepid review. About a month goes by and I had forgotten about that review when I agreed to interview Tom Cochrane about his band’s new record Cochrane phoned in from Allen’s office and the chat is going smoothly until Allen decided to read Cochrane my album review as I am conducting the interview.

Cochrane’s demeanour changed drastically. His feelings were hurt, he wanted to know how I could possibly question his lyrical insight and the end result is a frosty conversation. Subsequent interviews were a lot more cordial but Cochrane always ended our conversations with the same question. “Still don’t like White Hot”?

One band I never came to terms with in the Bruce Allen camp was Prism. Formed in 1976 by former Sunshyne trumpeter Bruce Fairbairn and the band’s drummer Jim Vallance in partnership with Seeds Of Tyme guitarist Lindsay Mitchell, the Prism band I witnessed at the Heart concert in Seattle was a seven-piece blues rock outfit that boasted a horn section.

By the time they recorded their self-titled debut in May ’77, Prism had been transformed into a five-man rock band with Ron Tabak handling lead vocals, Mitchell on guitar, Tom Lavin on bass, Vallance on drums and John Hall on keyboards with Fairbairn retiring behind the console to embark on a highly-successful career as a record producer. Over the next four years, Prism tinkered with their line-up, replacing Vallance with Seeds Of Tyme’s Rocket Norton and his bassist band mate Al Harlow replaced Tom Lavin who fronted his own Powder Blues Band.

Record and radio success for albums like “See Forever Eyes” and “Armageddon” and singles like `Flyin’, `Spaceship Superstar’ and `A Night To Remember’ ensured a decent profile in arenas across Canada but Prism never caught on in the States and their live show was pretentious to say the least. I had seen the band play live several times during my stint in Calgary and one aspect of their show always amused me. Now it’s a given most headline acts take an encore. It’s built into their set list, normally saving their big single or current hit for the grand finale. Yet Prism took numerous encores whether they were warranted or not.

I distinctly remember a concert in Calgary, probably at the Corral. “Armageddon” was huge at the time. They performed their basic show with the obligatory smoke bombs and pyrotechnics received a polite closing applause – yet were back on stage for an encore before the clapping had even died down. So they do their encore, (which was probably `Armageddon’), get another smattering of applause, and they run back on stage for a second encore – which was definitely not requested. Prism ran through another song, received even less applause than their previous song and off stage a third time.

With the house lights down and no sign of the sound man leaving his board, it seemed Prism were coming back for a third encore, when some wag in front of me stood up and screamed at the top of his voice. “Would everyone please shut the f**k up. Otherwise we’ll be here all night.” I thought his reaction was priceless….and Prism declined to take a third encore.

Bruce Allen knew there were serious limitations to Prism. Lead vocalist Ron Tabak had a stutter, which made him useless with the media plus he didn’t contribute any song writing material and was supposedly in trouble with gambling debts. With Vallance in dispute with Mitchell over the band’s song writing direction, and internal conflicts raging within the group, it didn’t help Prism were looking for a new record company after GRT pulled the plug in 1979. But Allen, being Allen, pulled a fast one on Capitol, convincing the label that as “Armageddon” had been such a big seller. Prism should receive a major multi-record deal. Capitol agreed with the caveat being he also takes management control over Red Rider to keep them away from the sweaty grasp of Anthem Record’s Ray Danniels.

[youtube width=”600″ height=”450″ video_id=”xp9852hq0W0″]

A strange thing began to happen after positioning the book with Records On Wheels. We started receiving subscription requests from strange countries like Argentina, Ecuador, Brazil and even European nations. But how were these countries receiving our magazine? The answer came when an individual (who shall remain nameless – but you know who you are!) explained Records On Wheels, illegally shipped product to foreign countries and used to pack these boxes with copies of Music Express. For the uninitiated, it was (and still is) illegal to export records to foreign countries – but was an acceptable practice in Canada at this time.

Much was always made of a record going gold (selling 50,000 units) or platinum (selling 100,000 units) or even diamond (one million units). Much pomp and ceremony took place with the artist or group in question receiving a gold, platinum or diamond award. This became such a hype that if a particular record was falling a couple of hundred or thousand units short of their target, the missing numbers would be shipped internationally… declared as domestic sales and that plateau was achieved. Hence this is how Music Express started to reach global markets.

“When the thunder from above decrees that you move X amount of units, you had to be creative,” said former Capitol salesman Paul Church, who acknowledged illegally exporting units and storing product in warehouses was part and parcel of meeting those quotas. “There was a big hype about achieving a gold or platinum sales target for your releases so we did what we had to do to achieve those quotas. Everyone knew it was a bit unethical but it was an accepted practice so we all used whatever means was available to shift numbers.”

Advertising wise, major labels were hit and miss depending on the release of key Canadian labels but our lifeline were the indie labels that all had major domestic records that attracted our support. Canada’s most influential domestic label was Anthem Records, home of Rush, Max Webster, Ian Thomas, Wireless and Aerial. Operated originally by Ray Danniels and Vic Wilson, Anthem’s initial office was located at this funky Oak Ridge’s farm house. To be honest, I wasn’t initially a big fan of Rush. In my Calgary Herald days, Eugene Chadbourne pitched me a copy of the band’s second album, “Fly By Night” and my first reaction was to notice an eight-minute song called `By-Tor And The Snow Dog’ – and I though nah! I can’t handle this.

Rush subsequently built quite a following with “2112” and “A Farewell To Kings”. PolyGram’s Ken Graydon convinced me to check them out when they played The Corral in 1978, but even though the crowd support was enthusiastic, that strange looking bassist (Geddy Lee) with that high-pitched voice singing `Closer To The Heart’ did nothing for me.

Yet as I started to visit Anthem, Danniels and sidekick Tom Berry played me their latest demos and I started to relate to their instrumental talents and complex lyricism. I remember Berry playing me a demo of `The Spirit Of Radio’ (from “Permanent Waves”) and me feeling the same sense of anticipation and excitement that those new tracks would generate. I subsequently got to interview Lee, drummer Neil Peart and guitarist Alex Lifeson and became a fan as I found a new appreciation of their musical sensibility.

[youtube width=”600″ height=”450″ video_id=”dm9xYkLxW0Y”]

I first heard of Max Webster when Boyd Tattrie tipped me off about this Sarnia Ontario outfit’s debut album and insisted on writing about the band for Alberta Music Express. When they released their follow up “High Class In Borrowed Shoes” in 1977, Ray Danniels called me and asked if I was interested in helping out on publicity for their Western Canada opening slot for Styx. So I tapped up my regional writers, Mitch Potter in Winnipeg, Graham Hicks in Edmonton, Tom Harrison in Vancouver and myself in Calgary and we started to put the word out on this eclectic outfit. Featuring them in the magazine wasn’t a problem but I also wanted to get airplay for them so I hauled in my buddy Tommy Tompkins who was still at CKXL at the time.

He agreed to interview the band on air, I pulled up outside the studios with the band in-tow but then Tommy claimed he had forgotten about the interview and couldn’t squeeze them on to his show. With the band, waiting patiently outside in their Econoline van, I called in a favour, pleaded with him to just give the band like five minutes and play their new single ”Diamonds, Diamonds’. Taking pity on me, Tompkins relented, begged for five minutes to speed read through their bio and invited Kim Mitchell and Co into the studio where they engaged in a pleasant chat and he did play their new single.

Attic Records, formed in 1974 by Al Mair and Tom Williams, proved to be Canada’s most industrious domestic label with a major roster of Canadian talent. Fludd headlined a list of talent which also included Triumph, Lee Aaron, Patsy Gallant, Hagood Hardy, Anvil, Downchild Blues Band, Teenage Head, The Diodes and Haywire, covering a vast repertoire of music genres. If a form of music was happening, be it blues, punk or heavy metal, Attic was in there. Mair in particular was receptive to Music Express. I had given Patsy Gallant one of our first covers and we were also on top of Teenage Head and Triumph in our music coverage. Al always wanted to play Monty Hall in negotiating ad rates but he was one of the first label managers to actively support ME.

True North, run by the two Bernies’, Finklestein and Fiedler were a throwback to the late Sixties, Yorkville era and their major acts, Bruce Cockburn, Murray McLauchlan and Dan Hill never fell into the rock star category that excited the masses. Yet Music Express provided editorial for all three with Dan Hill’s `Sometimes When We Touch’ single, registering international success. We were also on board when Finklestein went against rote by signing the controversial Rough Trade.

The revolving Sparkles disco atop of the Toronto CN Tower served as the venue for the launch of a third major indie label that summer. Solid Gold Records, operated by Steve Propas, Ed Glinert and Neil Dixon debuted to the industry with the introduction of the band Toronto and their debut album, “Lookin For Trouble”. Fronted by Annie (Holly) Woods and featuring guitarist Brian Allen and Sheron Alton, keyboardist Scott Kreyer, bassist Nick Costello and drummer Jimmy Fox, Toronto connected with their fiery Heart-like image fuelled by an impressive debut single, `Even The Score’.

[youtube width=”600″ height=”450″ video_id=”gYzySRvLD_0″]

Showing the label wasn’t a fluke, Solid Gold registered three consecutive platinum albums with Vancouver’s Chilliwack also racking up sales with their “Wanna Be A Star” album in 1981 and the Chilliwack spin-off band, The Headpins, launched by Brian (Too Loud) McLeod and bassist Ab Bryant, starring lead vocalist Darby Mills with their debut “Turn It Loud” release in 1982.

They also released records by The Good Brothers and imported releases by British bands like Mama’s Boys and Girlschool. Dixon, Propas and Glinert were great to work with, both on advertising support and editorial content. It was always an adventure going to their office on Bloor West near Avenue Road. The SCTV office was one floor above them so on more than one occasion, I found myself squeezing into the elevator with John Candy or Joe Flaherty.

Outside of Toronto, Montreal’s Aquarius Records was another early Music Express supporter. Formed by legendary promoter Donald K Donald Tarleton, he recognized Montreal needed its own major indie label. My first visit to Aquarius occurred when Music Express was still based in Calgary. I dropped by their office which was still in Old Montreal near the docks. Met Keith Brown and also members of Teaze, who I had seen previously open for Aerosmith at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1979. Future trips to Montreal always included a visit to Aquarius which moved offices to a more modern structure on the Cote De Liesse. Again, Flood and Brown understood the value of Music Express and always promoted the latest April Wine releases via ads and feature stories.